GUEST POST FROM DEZENHALL RESOURCES, EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, JOSH CULLING

In 2016, I wrote a piece for World Trademark Review in which I examined the components of corporate reputation and offered some advice to brand managers on how best to prioritize these when restoring a company’s reputation after a crisis. One key takeaway: C-suites are often misaligned with the publics they seek to influence and thus misdiagnose their reputational vulnerabilities.

WTR asked me to write a follow-up this year on a similar topic, which was published on May 19. The timing dovetails nicely with the release of the second edition of Eric Dezenhall’s book on crisis and reputation management Glass Jaw. I helped Eric with a few of the new chapters; you should buy it!

We decided to reissue Glass Jaw because my goodness has the media, PR and reputation landscape changed in the last six years. In my current piece for WTR, which I’ll be republishing excerpts of over the next few weeks, I examined a topic that we didn’t spend much time analyzing in Glass Jaw: human polarization and its implications for brand managers and corporate leaders.

I try to include as much practical advice as possible, but that can be difficult when each corporate crisis or reputational threat is unique. And when many C-suites are getting the very components of reputational risk wrong, diagnostics are as crucial as action items.

Note: WTR is a British publication, so they swapped out all of my z’s for s’s and added random u’s to some of my words. I apologize for the haughtiness.

###

The world has changed dramatically in the last six years, especially when it comes to how people access, analyse, share and respond to information. This is often oversimplified as a Donald Trump phenomenon; his rise to the most powerful office on Earth was defined by his uniquely and inherently optimised social media presence, and his presidency could be characterised as one long Twitter argument between two sides that were never going to agree on anything.

Whether Twitter was to blame or to thank for Trump is beside the point. We should think of him as the optimal example of how the modern exchange of information breathes life into causes, ideas and champions that would probably have been dismissed out of hand two decades ago. Since voters and consumers are essentially engaged in the same behaviour of evaluation and selection, there are plenty of lessons for corporate brands from the American political experience of 2015 to 2021.

The theme of this particular cultural moment is polarisation. There are several theories as to why, but the most compelling to me is the idea that there is an extremely lucrative market underlying the hardening of personal opinions and beliefs. The fortunes of digital media companies and connected platforms rise and fall on the amount of our attention they earn. More eyeballs means more revenue. Add engagement into the mix and you are really making money.

This is great if you run a marketing agency. The amount of hyper-targeted data on consumer preferences, motivations and actions available to anyone selling a product or idea is unbelievable and multiplying by the day. In exchange for our carefully cultivated universe – soon to be metaverse – of content that delivers quick hits of dopamine to our brains, we are sharing nearly invaluable data with platforms, which swiftly monetise it.

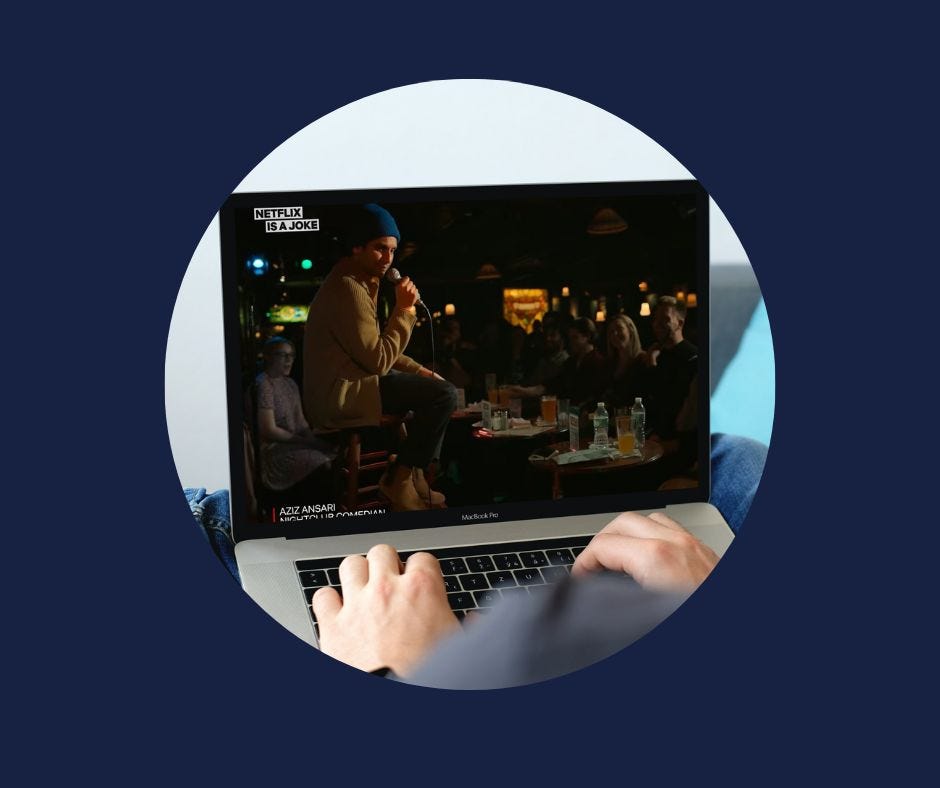

But because polarising, self-reinforcing content tends to attract the most sustained attention and engagement, the general public have hardened beliefs and attitudes, less likely to be persuaded by an opposing viewpoint than ever before. Comedian Aziz Ansari said it best in his recent Netflix special, when discussing American football player Aaron Rodgers’ and singer Nicki Minaj’s scepticism towards covid-19 vaccines:

I don’t think him, Nicki Minaj, any of these people are idiots. I’m not here to say that…I just think they’re trapped in a different algorithm than you are. You know what I mean by that? And if you’re calling them idiots and stuff, you’re trapped in another algorithm. I know everything you’re going to say about everything.

Commentary about social media and polarisation can reach moral panic levels and is often overblown as a harbinger of moral decline. I do not view this phenomenon as an unmitigated disaster but rather instructive for those seeking to persuade anyone of anything in the current culture.

I also do not view it as an explicit criticism of social media, technological innovation, AI or the other tech sector bugaboos. The same incentives influencing social media companies and digital advertisers apply to the traditional news media – CNN requires eyeballs, and it needs to know its audience, just as much as Facebook does. This analysis simply acknowledges that information is moving faster than it ever has before in human history and that the ultimate gatekeepers have changed dramatically in the last 20 years.

Given this, here are some diagnostic truths to consider when assessing your own reputation:

The median consumer is more likely than ever before to approach a controversy with preconceptions about its main actors.

It is harder than ever to persuade someone to change their mind.

Online reinforcement of one’s worldview often leads to unchallenged groupthink offline.

The nature of debate – and its implications for corporate reputation – is as unpredictable as ever.

###

Over the next two weeks I’ll be sharing the rest of the article, which dives in-depth into each of the four truths listed above.