I like movies about journalism because I live these dramas and enjoy comparing what I see on the screen with what I’ve experienced. I just watched She Said about the Harvey Weinstein scandal because I read the book and have worked on #MeToo issues. The movie was based on the book of the same name by the New York Times’ Megan Twohey (Carey Mulligan) and Jodi Kantor (Zoe Kazan).

While I like to needle my reporter friends about puffing up their importance, had Twohey and Kantor not stopped Harvey Weinstein with kinetic force, he would have kept going. Guys like Weinstein believe they’ve got a good thing going, no matter how sickening the rest of us think it is. They hire crisis managers because they want to be beloved as the gentle, misunderstood souls they most assuredly are not. That’s how they see crisis managers — as accomplices who can work their magic so they can continue doing what they want to do.

There was something I remember about the book that didn’t make it into the movie: the authors caution that all allegations should be pressure-tested for veracity because there is a danger of innocent people being destroyed by adversaries capitalizing on a moral panic for their own reasons. These are my words, not Twohey and Kantor’s, who underscored that the job of investigative journalists is to investigate, not traffic in trends. Weinstein was no such misunderstood victim; he was a beast whose rampage of terror should never have been allowed to occur. It was allowed because people who want to make it Hollywood, which seems like most of the population these days, didn’t want to tick off the guy who might make their movie or put them in it.

Absence of Malice is my favorite reporter movie because it showcases what I’ve seen constantly happening throughout my career: An ambitious journalist develops a missile lock on a target, needing that target to be an emblem of evil that must be destroyed based upon a belief. A kernel of possibility and attenuated connections are conflated with evidence. Given that the First Amendment permits the publication of almost anything, the story goes forward. In Absence, Sally Field’s reporter wrongly suspects that Paul Newman is a criminal because his father was one.

The best aspect of the film, to me, is that it highlights a point that almost no one outside of the very small world that follows defamation issues understands: the media can publish almost anything they want if they leave no paper trail demonstrating a conspiracy to knowingly harm a target based on falsehoods. Needless to say, malice, as the film tells us, a state of mind, is a very hard thing to prove, which is why the First Amendment is safe and sound.

Journalism movies do a decent job of laying out versions of a formula I presented in a book more than 20 years ago about how news stories are packaged. There is always a villain (bad guy), a victim (vulnerable person or group), and a vindicator (hero). These characters are usually unambiguous, as in She Said: Villain = Weinstein. Victim = Women Weinstein assaulted. Vindicator = New York Times.

In Absence, the players are less clear. The original villain (Newman) turned out to be a victim. There were a few surprise victims, too. And the vindicator (Field) became somewhat of a villain. This brings to mind other people and organizations who have been unnecessarily villainized in the press in real life: the Duke Lacrosse kids, University of Virginia dean Nicole Eramo, Richard Jewell, Bayer’s Roundup product, Chevron in Ecuador, Amanda Knox, Nick Sandman, Obama being foreign-born, Trump and Russia collusion and plenty of others.

Another favorite movie is Shattered Glass because it demonstrates the insidious side of journalistic ambition when the real reporter Stephen Glass fabricates stories in the New Republic to win praise and advance his career. Until I began writing investigative non-fiction and saw how hard it was to document a thesis, not to mention getting anyone to read it, I never understood the temptation. Glass wanted the awards but didn’t want to do the work — something for nothing is the great American curse.

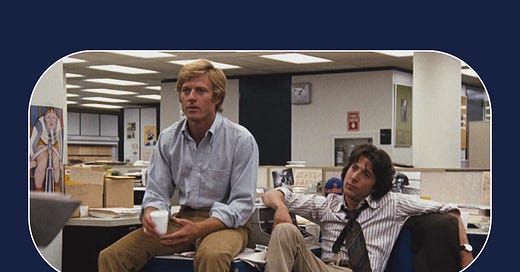

Of course, All the President’s Men, is the Rosetta Stone of journalism movies for multiple generations. It not only was anchored in the Villain (Nixon), Victim (the American public), Vindicator (Bob Woodward, Carl Bernstein and the Washington Post) formula, it established the journalist as a giant slayer and Marvel Comics superhero. This was both good and bad: Good because it inspired great journalism; bad because it taught many the wrong message, namely that all takedowns are accomplishments per se.

Given that the standards of journalism have fallen — I once had a young reporter tell me that the First Amendment permitted them to see my confidential client files — and the speed of news is more important than accuracy, it is likely that the next wave of media movies will emphasize defamation litigation over reporting procedurals. As I wrote in the revised edition of Glass Jaw (with Josh Culling), the future of the media components of crisis management is more likely to be in defamation law, not public relations.