Another poll was recently released on how the reputations of certain companies had slipped in the proverbial rankings. One of the companies named was Disney.

I was less concerned about the rankings themselves than I was about the commentary of a pollster who concluded that Disney’s reputation had fallen because the company appeared “calculating” in what they stood for in the wake of the Florida legislation debacle and that other companies were being rewarded for “taking a stand” on social issues.

Here’s my problem: Pollsters and communications vendors engaged in business development have a habit of drawing inferences about how people think without necessarily knowing what people are thinking. In reading what was available about the study, I didn’t see the basis for reaching these conclusions. To these ends, there are both utilities and deep flaws in polls of this nature, including recipients not wanting to go on record with their uglier impulses.

There is a circularity to all of this: 1) Opinion research is released showing a company’s rotten reputation 2) conclusions are reached that the reputational damage is due to the failure of the company to embrace the narrow agenda shared by most image buffers 3) PR firms are retained to advise companies on how to be better-liked, and they recommend campaigns often including school bus tours or digital advertisements with a corporate logo dancing above a meadow 4) like-minded special interest groups are funded to enter the fray, theoretically in support of the agenda in question 5) campaigns are undertaken that sometimes give reputations a bump by some suitable calibration designed to “measure success” and 6) lather, rinse and repeat.

Having been a party to hundreds of efforts of this nature, this opinion research doesn’t tell us the extent to which corporate reputations drop because consumers don’t want businesses mucking around with the narrow political agendas embraced on Madison Avenue and Wilshire Boulevard. Nor does such research address how many companies successfully dodge getting jammed up in social debates — and remain unscathed.

Of course, there isn’t a lot of money to be made in conflict avoidance.

Some of the best decisions to avert minefields are made based upon the instincts of smart executives rather than extensive polling, partly because these executives are beginning to feel abused by what they see as a racket to benefit consultants and the special interests that benefit downstream.

Among the things aggravating this phenomenon is the growing fetish for quantifying results independent of what these results actually tell us. Oftentimes, the wrong items are quantified. Hits to websites, verbatim responses to tactics, and the number of ad placements can be deemed a success in place of the real win, getting the critic off your back. Surely, clients are entitled to know what they’re getting for their money, but this has led to the emergence of initiatives whose primary benefit is their quantitative attractiveness so that they can be justified to the purchaser of services.

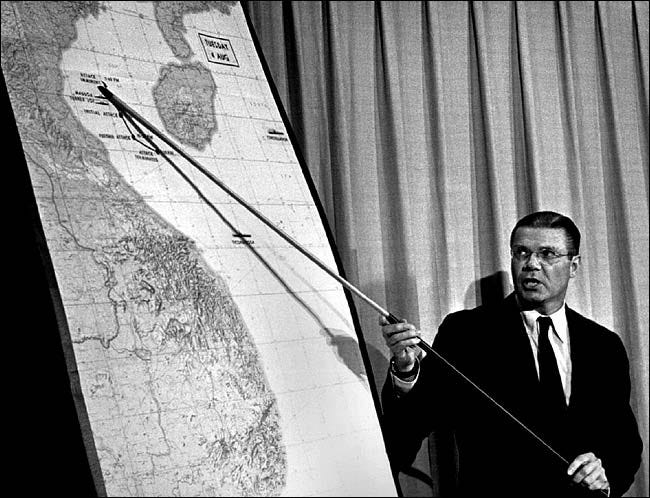

This is reminiscent of Vietnam-era Defense Secretary Robert McNamara’s cavalcade of charts done by his Whiz Kids. The charts depicted the number of bombs dropped, damage calculations, and inventory comparisons of men and ammunition against North Vietnam as if these things could measure and ensure victory. While doing all this, they were overlooking an unquantifiable reality: Those people really, really didn’t want us there and were committed to driving us out, which they did.

None of this should be interpreted as an endorsement of the “go woke, go broke” meme, which I have rejected in repeated writings and discussions. What I am saying is that we’re on terra incognito here and rigid conclusions cannot yet be responsibly drawn.

Not everything worth doing — or not doing — is especially measurable. Some of the most successful initiatives of my career have been rooted in what was avoided rather than what was demonstrably gained. And some of the best counteroffensives will never appear in a case study or be applauded by ESG or CSR dogmatists.

Furthermore, many of the problems companies face in this climate have been aggravated by the very industrial complex that’s supposed to guide them toward wise decisions. Communicators are understandably desperate to bring order to the Dodge City media and cultural climate we’re in. But the same experts that have been so talented at gauging or manufacturing sentiments when it comes to buying consumer goods and services have become mired in narrow political agendas that yield no business or social dividend.

As I recently told a client — to the horror of some in the room — “In between the Upper West Side and Sausalito, there is apparently some real estate that you should be aware of…”